Life at No 4 Havelock Square: Broomhall, Anarchy and The Commune

Written by Dave Lee

“Broomhall was the area I moved to when I first left home. I got a bedsit room at the upper end of Broomspring Lane, for £2.50 a week, in Autumn/Winter 1970. I worked at Viners cutlery warehouse on the Hanover Way near the underpass.

I had friends around that area, a whole social world. My contact with the anarchist scene had however started earlier. From 1968 I’d been going to a regular anarchist meeting, an informal discussion group in a long-demolished pub, The Albion, on a long-gone street (Albion Street?) behind the Brookhill shops. Amongst the people I met there were Dave Jeffries and T. Dave helped organize the University Anarchist Group, which had been going since around 1965/66. He sported long hair, and was articulate and friendly. T was visually impressive, with a big, spade-shaped beard, and a brash self-confidence to match. He was a shop steward at Acheson Electrodes in Owlerton, and the most famous and noticeable member of the Sheffield anarchist world.

Many of us went on demos; everyone of my generation will remember the anti-Vietnam war demo in 1968, in which we marched from Tinsley Wire on Attercliffe Common, a company that made barbed wire for the US military, to a rally in Barker’s Pool. Thousands of people turned up. At the demos, it was always the Trotskyists (mainly IS, later SWP) who tried to run it all. They wanted the Communist North Vietnamese government to win, which as far as we were concerned meant supporting yet another authoritarian regime. We’d all sing along ‘Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?’ and we’d add ‘Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh, how many more did you do in?’

We went to an anarchist conference in Hull in 1969 or ‘70, where I was introduced to Albert Meltzer, editor of Black Flag and organizer of Black Cross, who’d been smuggling arms to the Spanish Anarchist forces while still in his teens.

What is anarchism? It is fair to say that there as many different version of anarchism as there are anarchists, but they tend to share the following features: opposition to all forms of government and advocacy of a society based on voluntary cooperation of individuals and groups.

T’s position at the time was that anarchy (which is to say the enactment of anarchist principles) involves three strands: for the workplace, anarcho-syndicalism (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anarcho-syndicalism); for theoretical discussion, nihilism (in the original sense of no idea at all being immune to enquiry or rejection); and for home life, communism, in the sense of collective ownership and non-coercion. He spoke of starting a commune.

By the time I moved to Broomhall, the Commune was already established, with its first group of communards. This must have been Autumn 1970. T had bought a three-bedroom terraced house at 4 Havelock Square(1), later Holberry Close. I went round a few times. The first time, I remember people sitting by candlelight. I met Bob Gilpin, Barbara, Pete Green, Dick Keaton and Geoff Hoare. On another visit I met Pat, T’s girlfriend. She had decorated the bathroom walls with polystyrene tiles painted in black and orange, like a Halloween mosaic.

At my Broomspring Lane home, I fell out with the landlord, who lived on the middle floor. Now, I can understand his objection to my late music, played on a portable Dansette record player. I moved round the corner to Havelock St. That didn’t last long, the landlord didn’t like my moving superfluous furniture into the corridor.

In those days, we’d given up on living 14″ above the floor. Rooms were easy to find, and moving did not require a car, if you had as few possessions as I did. Portable record player in one hand, suitcase (later rucksack) in the other, containing mostly books and records; an overcoat on, on a hot day. My mum’s attic held the rest. (Why do people pay for storage now? Self-store places were pretty much unknown then.)

My next move was into the very corner house of Brunswick Street and Havelock Square, which was later renamed Holberry Place as part of a rebranding of the area. Broomhall was no doubt rebranded because of its reputation for illegal drinking and prostitution. To us, Havelock Square was simply The Square, and it was the heart of a tolerant, vibrant area. The illegal West Indian clubs known as the Blues, where you could listen to loud reggae and have a drink after the pubs, were largely tolerated by the police, and were superb for racial harmony.

Further landlord trouble made me decide to move again. T offered me a place in the Commune, currently only occupied by himself. I moved into the front bedroom, overlooking Havelock Square. Across the street, some friends of mine lived in number 9.

In my room was an enormous walk-in cupboard (behind the upper right hand window in the photo), which was full of books. Many of them were on psychiatry, the legacy of Roy Lilly, a friend who’d worked as a psychiatric nurse, and who’d lived there briefly. Many of the others were donated by Sam Simpson, towards a Communal Library.

I settled in quickly. It felt good to be part of something. T had bought a huge sack of pasta and, when cash was low, I often lived off of pasta with tomato soup and grated cheese.

The next person to move in was Phil Roddis. He was younger than me by a year or two. (T was five years older than me.) Phil worked in a bar in the centre of town.

One night T and I went to a party in Crookesmoor, and met another Phil. He was the next to move in. I shall refer to him for the purposes of this narrative as Phil 2. A third Phil visited and stayed for a while – Phil Green, who was a kind of travelling anarchist contact in those days, hitching the length and breadth of the country and visiting anarchists. He was vegetarian and his speciality was vast dishes consisting of many different varieties of beans. At some stage, Canadian Lynn moved in and stayed a few months, on and off.

A regular visitor was Chris Tetsall, who subsequently bought a house round the corner on Monmouth Street, adding to the range of local anarchist households you could visit. Anarchist ideas and practices were networked (although that term did not then exist) by hitchhiking and informal meetings, or just turning up somewhere like Leeds Claimants’ Union and learning from them.

T established a couple of principles for the Commune which persisted through most of its life, if not all of it. The first was that the door was never locked. The second was that no-one was ever turned away. These policies remained in force, certainly all the time I lived there. Once, Phil Roddis brought home from his bar job a young runaway, whom we put up for a while, and on another occasion, a major supplier of acid from London.

There was lots of discussion in those early days. Anarchism has always had an uneasy relationship between ‘what could be’ and how to achieve that better society; it’s perfectly clear to anarchists that insurrection does not generally produce a better society. Communists used to pretend that the Soviet Union was something much better than it actually was. Insurrection is not revolution, merely a change of oppressors, the same basic coercive, violent, exploitative mechanisms are still in place after the state comes under new ownership.

So we didn’t see our role as selling papers or building an organisation aimed at insurrection. Instead, what we were doing was about everyday relationships, breaking the patterns of bourgeois society to underpin a new kind of social movement.

A quote from Murray Bookchin (his 1971 book ‘Post Scarcity Anarchism’ (2)) gives the flavour of the anarchist theory of the day.

‘The great historic splits that destroyed early organic societies, dividing man from nature and man from man, had their origins in the problems of survival, in problems that involved the mere maintenance of human existence. Material scarcity provided the historic rationale for the development of the patriarchal family, private property, class domination and the state; it nourished the great divisions in hierarchical society that pitted town against country, mind against sensuousness, work against play, individual against society, and, finally, the individual against himself.’

This kind of anarchism emphasized total cultural transformation, via transformation of everyday life. Bookchin admired features of the youth subculture of the day that would nowadays be derided as hippy values. Many people in that anarchist milieu took LSD, which was very easy to acquire. In fact, it would be fair to say that much of our social scene floated on a small lake of LSD. And the people I am talking about were not the pop-mystics that psychedelic culture has become associated with; there was less of an emphasis on achieving ‘enlightenment’ and more on living true to ourselves. We were inspired by the Situationists, the French group who embraced a new view of capitalism, critiquing the way in which it weaves a web of illusions, the ‘Consumer Spectacle’, which ensnares us all.

My first encounter with Situationism was intense and dramatic. I was high on LSD, and undergoing a confused phase when my friend Big Ben thrust a copy of ‘King Mob Echo’ (3) into my hands. KME was the current journal of the London Situationists, and it was full of loaded quotations. The opening of an article entitled Desolation Row leaped out at me and cleared the confusion in my mind:

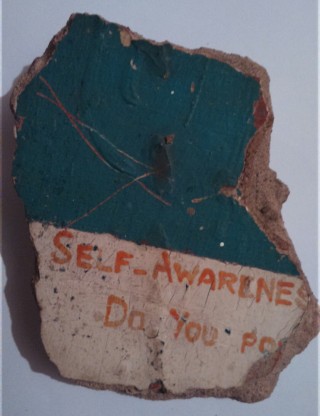

‘Rozanov’s definition of nihilism is the best: ‘The show is over. The audience get up to leave their seats. Time to collect their coats and go home. They turn round… No more coats and no more home.’ Nihilism is born of the collapse of myth.’ I made a poster-size copy of a crazed cartoon (4), and hung it on the living room wall. That wall had quite a few statements and questions on it. The photo on the right is of a piece of plaster a friend of mine saved from that wall.

Acid infused us with a militant antimaterialism. On at least two occasions I remember taking it to go to anarchist conferences, one in Leeds and one in Sheffield. After the Sheffield one, we ended up being thrown out of Crookes Valley Park for skinny dipping. Some conferences were less playful. At one in York, an anarchist of my generation, Keith Nathan, announced the idea of a national anarchist organization, with card-carrying membership, the Organization of Revolutionary Anarchists, or ORA. It wasn’t clear to our contingent what he thought such a move would achieve. At some point, Nathan said ‘Our current level of organisation is as much use as a two inch prick.’ We were still left puzzled as to what exactly he planned to make love with, once he was equipped with a larger one.

Lifestyle revolution was to be cemented by having a communal bedroom. The first version of that was in the attic. Previously, the room had been a normal-sized attic room, used by Geoff Hoare as a bedroom. The wooden railings had been removed and room had a door sealing the entrance off, so you entered through a trapdoor. The walls were painted purple with great spots of other colours. I remember listening to John Lennon’s new album, the one with ‘Working Class Hero’ on it, as I painted white emulsion over everything. T and I ripped out the end plaster-and-lath walls and boarded the newly-exposed floor with scrap wood from the demolition of a corner shop (5)

The result was a large, bright space. It worked well as a communal bedroom, sleeping four or five people, quite often with bed-guests.

The second version of the communal bedroom was planned for the middle floor. This involved some structural alterations. We ourselves took out a plaster-and-lath non- structural wall, then T invited some alleged builders round to deal with removing the load-bearing central wall. We helped them knock out the top two course of bricks, and they slid in a RSJ.

When the steel joist was in position, we couldn’t help but notice that it was a bit short. It was only supported by the walls at each end by less than an inch of its length. However, the ‘builders’ said it would be OK and proceeded to bed it into the end sockets. After a considerable amount of clearing up, we would have our new communal bedroom on the middle floor. Which was just as well; nobody favoured the attic after that, because the floor bounced a little too much.

I asked a couple of friends if they’d like to move in. One considered it briefly but it seemed like the communal life did not appeal to most people. For one thing, the non-violence bit did not always work well. I recall two occasions where violence broke out between T and someone else in the house.

I’d come home from the University Student Union bar, just up the top of the road and a regular hangout for many non-student Broomhall locals, with my girlfriend and a couple of people we’d been talking with in the bar. While some of us were sitting in the front room, one of the guests and T got into a fight. Hearing some noise, I came through from the front room to a scene of mayhem. My student guest had a cut head, as a result of T bashing him with a pewter teapot, and you know how head wounds bleed. Feeling somewhat responsible, I went out for a taxi – the old Royal Hospital was nearby, on West Street. When I got back with the cab, the place was full of police. One of our student guests had been under the influence of LSD and, imagining that the juice from a jar of pickled cabbage that had got smashed in the struggle was blood in which the kitchen floor was swimming, had run out into the streets and got the police. The upshot of it was, we were busted for a small amount of hash and a few tablets of acid.

The next day, I hitched to Glastonbury, for the first free festival, June 1971. The bust was headlined in The Star local newspaper as ‘Tea Pot Assault at the Pot Smoking Anarchist Commune’. A headline for history.

One warm summer night, we went for a drink in the Raven pub, which was our favoured local. (It stood on Fitzwilliam Street, where the Revolution bar is now). Walking home, we got followed by a notorious local thug, Ray Weymouth I believe his name was. He was shouting abuse at new house guest Mick Thorpe. Everyone ignored it until Weymouth started calling us all losers. This was too much for T who, in his bare feet, turned on Weymouth and kicked seven shades of crap out of him. We were, needless to say, impressed, considering Weymouth’s reputation and T’s lack of footwear.

The aforementioned Mick Thorpe was a charming chancer, a stylish, engaging alcoholic, who came with warnings: Big Ben in particular insisted he would thieve from us. And true to form, during the time he stayed, he stole the household’s entire collection of LP records, some of which were mine, and tried, with some success to steer the finger of blame towards an occasional visitor. The truth only emerged after he’d left.

As that summer ended, the scene seemed to be getting less idealistic, more inward-turning. A number of people passed through the house, few of whom I remember having any real enthusiasm for the anarchist project. In the end I got sick, with what turned out to be hepatitis, and went into hospital in November 1971.

When I got better I moved in with my girlfriend, not being robust enough to deal with the daily stress of living at the Commune. I returned for my portable record player. It was part buried under the remains of a wall which had been knocked down, and not entirely cleared.

After I left, the Commune continued for years. This article has only really covered the period 1970-71. Below is a brief contribution to a subsequent history.

Later Timeline:

1972: T often invited people back for dinner, and maintained the open-door policy even after some rather violent characters started coming round – the Blue Angels biker gang. I knew one of them from when I’d worked at Brown Bayley Steels in Attercliffe, a man called Schultz whose right leg was steel below the kneecap. He was an interesting man to have a drink with, but his friends decided to wreck the house one day. I visited, to find the place thoroughly smashed up. Someone had taken an axe to the gas cooker.

1972-3: Other inhabitants – Black Bob (Mark) who wrote anarchist texts.

Barn – who also wrote for Sheffield Anarchist magazine (6), which was revived in 1975. The first of the new series – Volume 1, #11 – was written in part by T and distributed from the Commune.

1975/8?: Malcolm and Jenny lived there in this period.

1979?: T let the entire house to Liz, closing the Commune for the time being.

1984: Someone started a fire in the house. The resultant damage was so serious that no. 4 and the end terrace house no. 2 were both demolished. I daresay the structural integrity of the building was compromised not only by the arson attack but by the too-short RSJ which had been barely holding up the attic floor for thirteen years.

Aftermath and legacy:

We inhabitants (‘communards’) called it The Commune. Some people called it T’s Commune. Many people questioned whether it was a commune at all. To some people looking in, it might have looked like just one man’s household. But for at least some of those who lived there, commitment to social and political transformation was total.

What were my hopes? That what we were doing would spread into a movement, underpinning a new society, built from the ground up. The ‘alternative society’ was the phrase. Lifestyle anarchism, anarchy in action.

It was a worthwhile experiment. I learned a lot about how to live with other people and make do with very little, whilst having a great time. I learned that quality discussion and life-changing experiences could take place when there were few resources. And I was certainly not the only one. Literally hundreds of people must have stayed at the Commune during its thirteen-fourteen years, and many were transformed by the experience, coming to understand that other ways of living are possible. This is one of the important functions of any long-running radical project, to keep some kind of demonstration of differentness going in the face of apathy and conformity.

Eventually, the Sheffield Anarchist Commune became part of Sheffield anarchist history. The Anarchist History walks (later pub-crawls) advertised in Sheffield Anarchist always started from the Hanover House pub and made their second call at the Commune.

A big thank you to Sam and Charmian for conversations, photographs and that piece of wall.”

NOTES:

(1) For £760 apparently! This is not surprising – my parents bought a house in Hunter’s Bar in 1967 for £900.

(2) https://libcom.org/files/Post-Scarcity%20Anarchism%20-%20Murray%20Bookchin.pdf

(3) See numerous online resources, including http://malaised.blogspot.co.uk/2012/06/on-militant-art-part-2-king-mob.html, http://www.revoltagainstplenty.com/index.php/archive-local/93-a-hidden-history-of-king-mob.html

(4) http://www.worldpicturejournal.com/WP_4/Cooper_Images/Cooper_5.jpg

(5) Boardman’s was a long-serving corner shop on Broomhall St. They stocked fancy teas, and we learned that they used to have champagne, from back in the wealthy days of Broomhall. Boardman had a lifesize cardboard cutout of Eric Robinson near the front of the shop, some kind of marketing freebie. From the street at night, it produced a faint sense that someone was behind the door. Which must have discouraged burglars.

(6) Available from the Libcom archives: https://libcom.org/library/sheffield-anarchist-vol-1-no-11

Comments about this page

Hi Dave,

Yes, I think it undermined what little structure remained! Though the loss of Skylark’s annual birthday Blues perhaps meant there was less stress to the walls and floorboards than in the past!

The Commune was registered in the International Directory of Communes as The Sheffield Anarchist Commune, and as a result we did get a fair few people turning up who perhaps expected something slightly different to the reality!

The phrase ‘Communauts’ came from T, who told me it was preferred by some of the early inhabitants, who fancied they were on a journey akin to the moon-shots of the time 😉

All the best

Barn

Hey, good to hear from you Barn! And thank you for adding some more detail. I didn’t realise it was the demolition of #2 that caused the crumbling of #4.

I hope other ex-communards (or communauts!) add their thoughts.

Thanks for going to the trouble of writing this Dave, a very enjoyable trip down memory lane. Hope you and the many other former communards (or communauts I think) are well. I’m no longer in Sheffield, but still visit regularly, and still an active Anarchist.

My recollection is that T moved out of The Commune in 1983, after celebrating his 40th birthday there the previous December (which was quite an event as you can imagine). He moved in with his girlfriend of the time, in Exeter Drive, and later took over the flat, where he still lives I believe.

After the house next door, number 2, was demolished the result of the structural alterations began to show a bit, and pieces of ceiling regularly came crashing down. When someone visited from the council, they also discovered that the central pillar from the cellar was missing, and exited the house rapidly! The last inhabitant was a biker named Rick, who I think moved away from Sheffield. The Commune was subject to compulsory demolition, and I think T received a small amount in compensation.

There were several different Sheffield Anarchist Walks (or pub crawls), but I’m afraid I only ever got round to writing up one of them. We did visit both the Albion and Raven on at least one of them, in addition to The Hanover of course.

All the best

Barn

Add a comment about this page